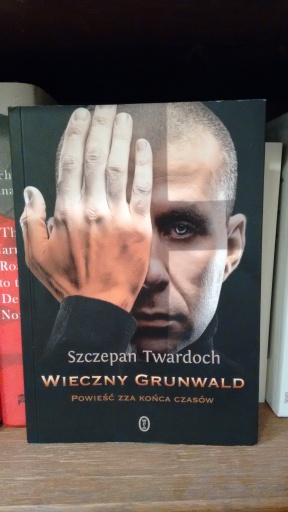

A RIVETING, EXPLOSIVE TAKE ON THE AGE-OLD POLISH-GERMAN CONFLICT.

Szczepan Twardoch’s novel Wieczny Grunwald (Eternal Grunwald), originally published in Polish in 2010, is the explosive tale of Paszko, a royal bastard who survives his own death in battle and traverses time and space as a metaphor for the centuries-old conflict between Poland and Germany.

Born in the late fourteenth century to a well-heeled German mother after her brief liaison with the Polish king, Kazimierz the Great, Paszko grows up in poverty among the inhabitants of a whorehouse. He is taken up by a client of one of these prostitutes, a famous knight, and trained in the art of combat. Paszko later joins the Teutonic Knights, and dies at the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg in German).

The Battle of Grunwald, fought between the allied armies of Poland and Lithuania and the Teutonic Knights, was one of the largest battles in medieval European history. The result was a decisive defeat for the Knights, and Grunwald became a keystone of Polish national mythology.

But Paszko’s death at Grunwald is not the end of his existence. Twardoch resurrects his hero, who differentiates between his own real existence (‘istne światowanie’) and his everlasting dying (‘przezwieczne umieranie’). The latter sees him inhabiting numerous Polish and German identities throughout history—and indeed in parallel realities—notably that of a Nazi-era German soldier. In every incarnation, Paszko is caught in the cycle of human violence, which he sees as an inevitable element of existence:

I nie wzruszam się, widząc tych, co własnem ciałem zasłaniają od bełta swoje dziatki, bo wiem—nie podejrzewam, nie sądzę, lecz wiem, bośm widział—że tak samo strzelali do dziatek pruskich […] I nie patrzę też na to jak na sprawiedliwą pomstę za tamte śmierci, po prostu patrzę: Spartanin zostawia swoje pierworodne dziecko na puszczy, aby umarło, Aztek rozrywa dziecięcą pierś, aby spadł deszcz […] a Prusak, ledwo co wychrzczony, syn poganina, zabija pogańskie dziecko nie z nienawiści. Czy to może przypadek je zabija?

[I do not feel anything when I see them defending their children from quarrels with their own bodies, because I know—I don’t suppose, I don’t think, I know, because I saw—that they shot Prussian children in the same way […] Nor do I look on it as on a justified revenge for those deaths, I just watch: the Spartan leaves his first-born child in the forest so that it will die, the Aztec tears open a child’s breast so that it will rain […] and the Prussian, only just baptised, son of a pagan, kills pagan children but not out of hatred. Could it be chance which kills them?]

Paszko’s narrative flits dizzyingly and exhilaratingly between memories of his first real incarnation—his mother, the bordello, his training as a knight—and his other existences. His everlasting cycle of death, rebirth and struggle enervates him, and he longs for a final death which is consistently denied him:

A ja nie chcę [żyć wiecznie]. Nie chciałem i teraz nie chcę, marzyłem tylko o tym, żeby nie być, żeby mnie nie było, a teraz jestem, wszechjestem, czy raczej coś mnie iści, nie ma formy biernej od być, jak może nie być formy biernej od czasownika być […] a mnie coś iści, wszebożek mnie iści, nie, to nie ja siebie iszczę, nie jestem, tylko wszebożek mnie wszechiści i samo to moje, lecz nie moje istnienie jest cierpieniem, i modlę się do wszechbożka, aby raczył mnie zakończyć, ale wszechbożek milczy, zawsze milczał […]

[But I don’t want to live forever. I didn’t want to, and don’t want to now, I only dreamed of not living, of not existing, but now I am, I am eternally. Or rather, something inhabits me, there’s no passive form of to be, how can there be no passive form of the verb to be […] But something inhabits me, the omnipresent god inhabits me, no, I do not inhabit myself, I am not, only the omnipresent god makes me eternally sentient, and all my-but-not-my existence is suffering, and I pray to the omnipresent god that he might deign to end me, but the omnipresent god is silent, he has always been silent […]

Twardoch’s novel is a work of great creativity, imagination and power, yet also dark, brooding and mysterious. The indigence of the Middle Ages, the violence and brutality of the knightly life, and the horrors of the Nazi regime are all captured brilliantly. Twardoch has created a pseudo-medieval Polish dialect to convey Paszko’s thirteenth- and fourteenth-century milieu, which delineates these parts of the narrative from those which deal with Paszko’s subsequent existences. The underlying theme of Polish-German relations, and the conflicts which have arisen between these two neighbouring peoples, shows how important the two countries’ shared history is even now, when the relationship is more cordial than ever before.

Published by Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2010, 210pp.

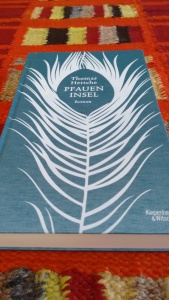

Marie’s life plays out against the changes which happen on the island and farther afield. Friedrich Wilhelm III engages Peter Joseph Lenné as a landscaper, and he transforms the island into a menagerie of exotic animals—lions, kangaroos, monkeys and other animals from far-away lands find a home on the island and amuse its inhabitants and visitors. Tropical plants find their way into the island’s greenhouses. The engineer uses the latest technology to create a complex heating and watering mechanism to sustain the unusual greenery. An African man and a Pacific Islander are also brought to the island and exhibited to visitors alongside kangaroos and lions. Away from the island, cholera decimates Europe in the 1830s, Berlin morphs into a modern metropolis—‘on the island they spoke of the city, of the immensely long streets made of nothing but stone, of the tenements as tall as castles, of courtyards and the innumerable people who laboured in workshops and factories, of canals and boats full of bricks and coal […] of beer gardens and political meetings, of suffering and hunger’ (p. 266)—and in 1848, Friedrich Wilhelm IV and his family flee political unrest and find sanctuary on the island. Later, the exotic animals are transported to the newly founded Berlin Zoo, and the island is deprived of ‘its longing and all its fantasies, which were the only reason Marie and her brother had been brought here’ (p. 263).

Marie’s life plays out against the changes which happen on the island and farther afield. Friedrich Wilhelm III engages Peter Joseph Lenné as a landscaper, and he transforms the island into a menagerie of exotic animals—lions, kangaroos, monkeys and other animals from far-away lands find a home on the island and amuse its inhabitants and visitors. Tropical plants find their way into the island’s greenhouses. The engineer uses the latest technology to create a complex heating and watering mechanism to sustain the unusual greenery. An African man and a Pacific Islander are also brought to the island and exhibited to visitors alongside kangaroos and lions. Away from the island, cholera decimates Europe in the 1830s, Berlin morphs into a modern metropolis—‘on the island they spoke of the city, of the immensely long streets made of nothing but stone, of the tenements as tall as castles, of courtyards and the innumerable people who laboured in workshops and factories, of canals and boats full of bricks and coal […] of beer gardens and political meetings, of suffering and hunger’ (p. 266)—and in 1848, Friedrich Wilhelm IV and his family flee political unrest and find sanctuary on the island. Later, the exotic animals are transported to the newly founded Berlin Zoo, and the island is deprived of ‘its longing and all its fantasies, which were the only reason Marie and her brother had been brought here’ (p. 263).